Water Desk Grantee Publication

This story was supported by the Water Desk’s grants program, which operated from 2019 to 2023.

It’s just past noon on a Wednesday, but the bar at the Ski Inn in Bombay Beach, California, is already packed. The crowd is mostly Canadian, snowbirds escaping to the desert spas and country club communities that dominate this southeastern corner of the state, just 50 miles from Mexico. Bombay Beach is not their destination, just a side trip to see the ruins of the once-famous party town.

In the 1950s, Bombay Beach was a celebrity destination. Frank Sinatra, the Beach Boys and Bing Crosby frequented its luxury resorts perched at the edge of the Salton Sea, California’s largest lake. Lauded for its fishing, boating and water skiing, the Salton Sea attracted more visitors than Yosemite National Park. Birds, too, loved the lake, with thousands spending winters there every year.

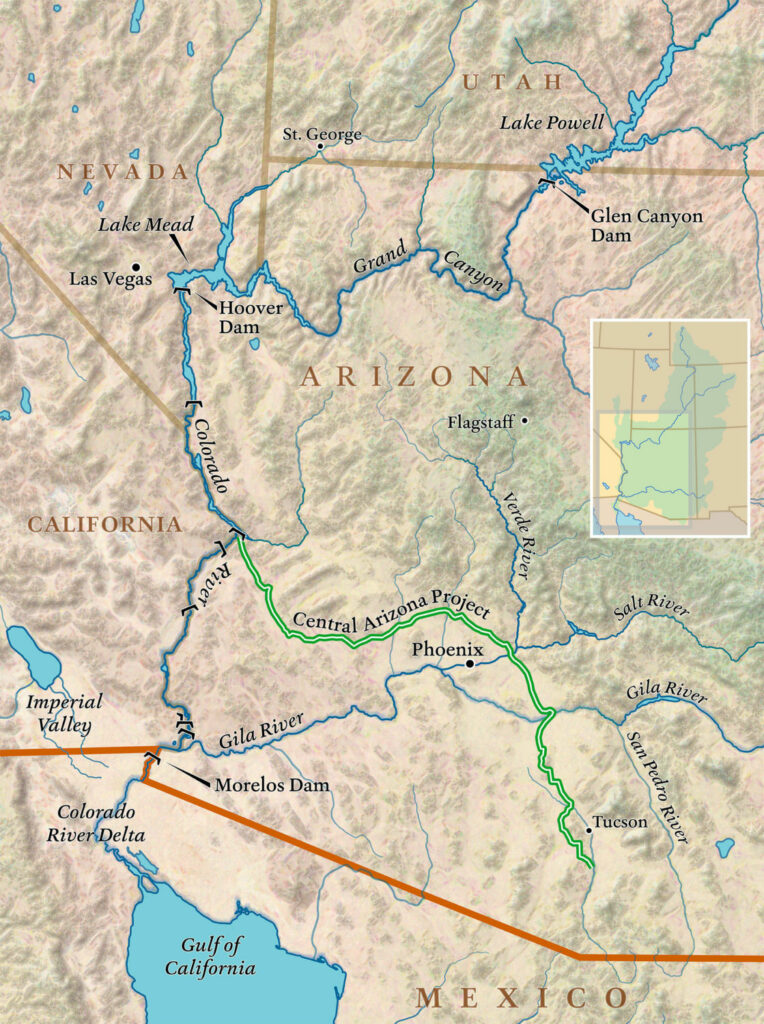

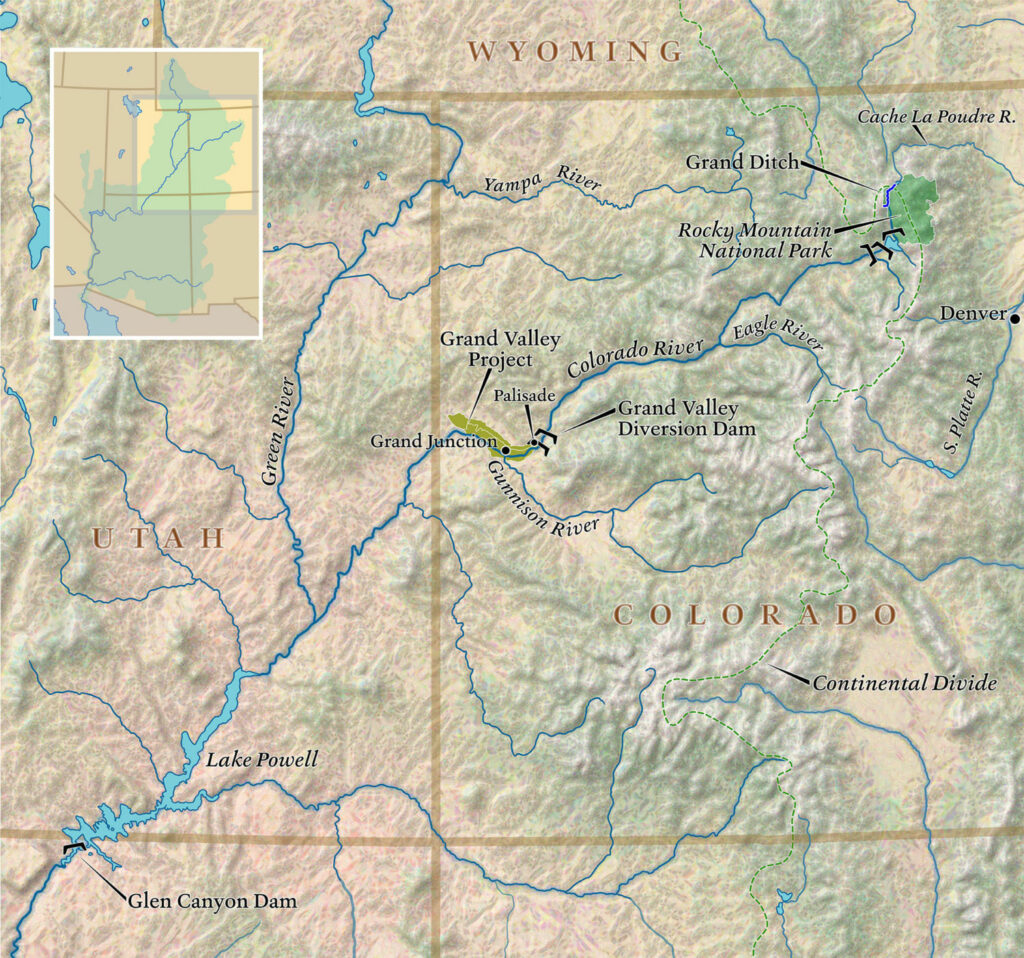

The lake was formed in 1905, after the Colorado River breached an irrigation canal and flooded the Salton Sink, a basin in the desert that has periodically held lakes throughout history. Once the canal was repaired, two years later, the Salton Sea had no source of water other than the runoff that flowed in from the nearby farms of the Imperial Valley, one of the state’s agricultural hubs.

This runoff water, full of chemicals and nitrates, was saltier than the lake water. As it drained through the soil, it combined with ancient salt deposits, raising the salinity even further, and in the 1970s scientists started warning that change was coming to the Salton Sea. The salt would transform the lake, causing it to shrink and making it inhospitable to wildlife.

Sure enough, before the decade was up, fish started dying off and bird populations declined. The lake began to stink, spurring the state to issue periodic odor advisories that sometimes extended as far away as Los Angeles. Today, the lake is about twice as salty as the Pacific Ocean.

“It’s a drastic change,” said Jane Southworth, the only local at the bar, who came seasonally to Bombay Beach before settling here for good in 1990. “It went from fun to no fun. From water to sand, or I should say mud.”

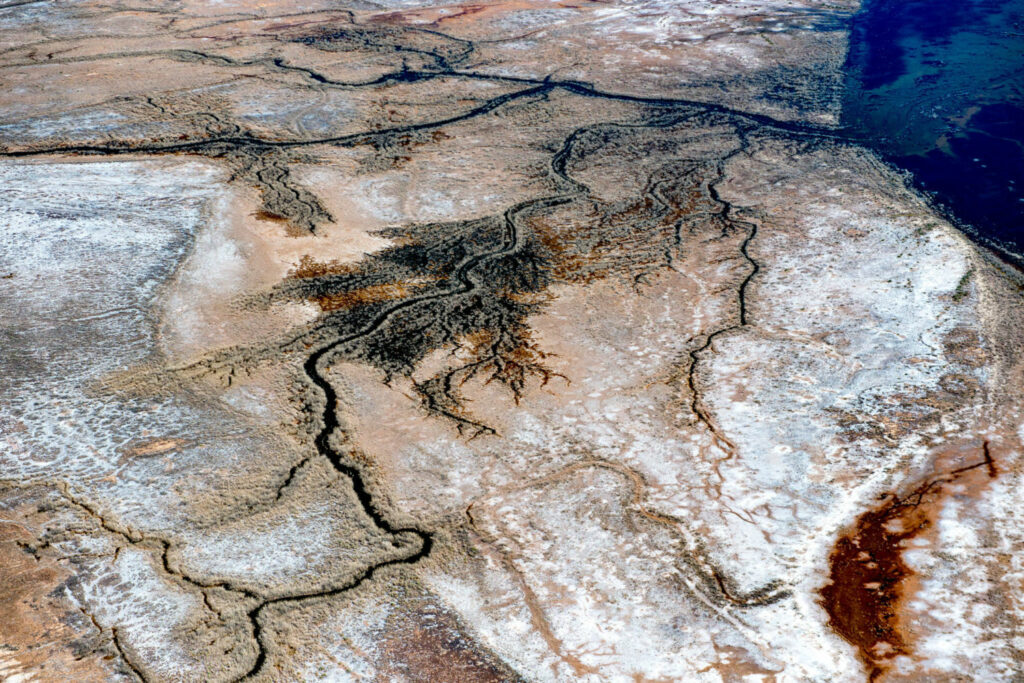

Now the Salton Sea has another problem: Climate change is making this dry region even drier. And a growing demand for water in the booming cities and suburbs of Southern California has reduced the amount of Colorado River water diverted to nearby farms. In the coming years these two factors are expected to dramatically increase the pace at which the lake shrinks, exposing more lake bed and the agricultural toxins trapped in the mud.

The desert winds lift dust from the lakebed, and scientists fear that eventually the toxic residue of more than a century of agricultural runoff will be blown into the air — and into the lungs of residents. The area surrounding the Salton Sea already has some of the worst air quality in the country, caused by particulate matter swept up from farms and the desert. Local residents have some of the highest rates of asthma and other respiratory problems in the state, and public health officials say the heavy metals and chemicals in the lake bed pose an even greater threat.

Many of the people and businesses that once relied on the lake have left, driven away by the smell of dying fish or the fear of health problems. Those who remain — farmworkers, families, the elderly — are generally too poor to afford the rising cost of property elsewhere in the valley. Others, like Southworth, who’s retired, have too many fond memories of the lake to give up on its future.

“I just wish they would do something, put some water out there,” she said.

A slow-moving disaster

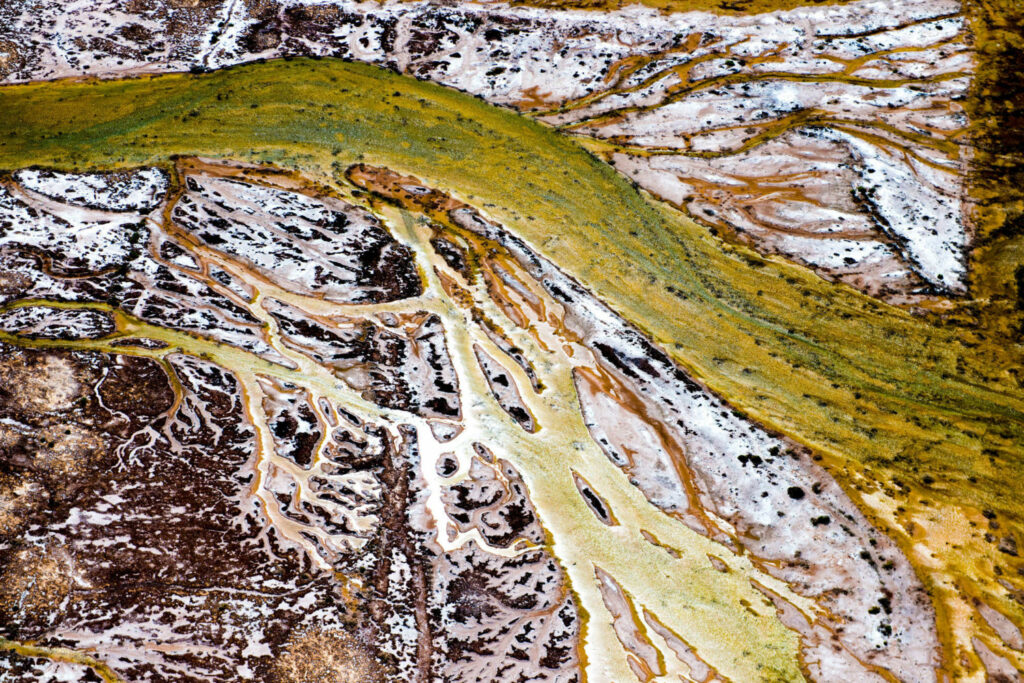

To understand the Salton Sea — its massiveness, its unlikely place in the desert of Southern California — it’s best to see it from above. In November, I boarded a four-seat plane with Frank Ruiz, the Salton Sea program manager for the Audubon society. We took off from a small airstrip in Thermal, north of the lake, and soon the lake flooded our view from the window.

It seems unnatural, the shimmering water surrounded by chalky sand and cactus. But water has found its way into this desert basin repeatedly throughout history. Before dams and other diversion structures fixed the Colorado River on its current path, the river used to periodically migrate across the floodplain, changing course to circumvent sediment that had built up in previous seasons. Sometimes it emptied here in the Salton Sink. During one such period, the river sustained an even larger lake, Lake Cahuilla, that stretched from the Coachella Valley, up by Palm Springs, all the way to northern Mexico.

We fly near the Chocolate Mountains that rise up south of the Salton Sea, and Ruiz points to a discolored line high on one of the ridges where a thousand years ago lake water once reached.

“If you talk to anyone from the Cahuilla tribe, the people who have been in this basin forever, they say water has always been here,” Ruiz said. “So this isn’t just about saving some artificial lake.”

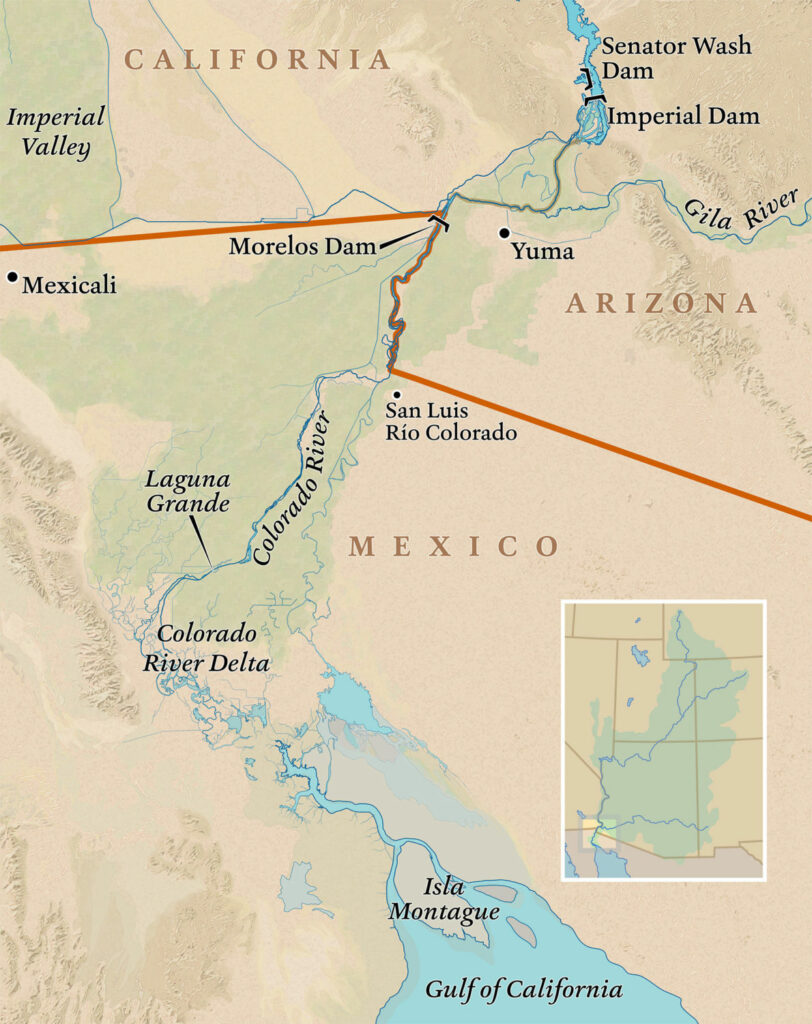

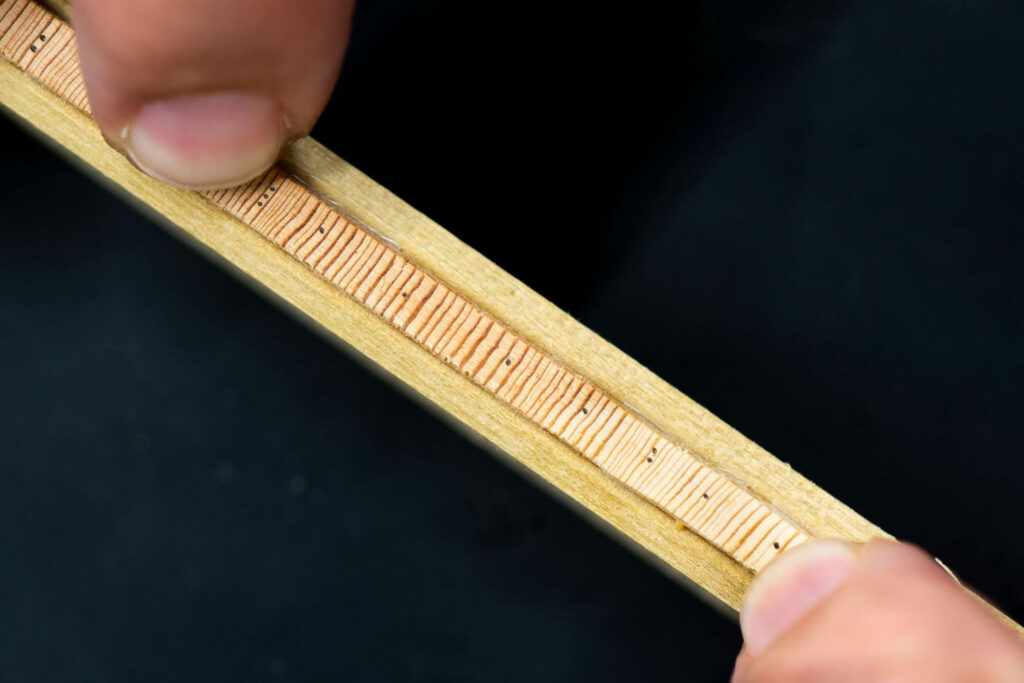

Lake Cahuilla dried up sometime in the 16th century after the river again shifted course, this time to the Gulf of California. Dams have tamed the river’s meandering, and it’s unlikely the Colorado will ever find its way into the Salton Sink again. Yet the river’s water is still coming, diverted into the desert via the 80-mile-long All-American Canal.

As the plane veers back, heading to the south side of the Salton Sea, more than 500,000 acres of farmland unfurl beneath us. This quilt of green is the Imperial Valley, home to some of the world’s most fertile soil, enriched with minerals from the Colorado River floodplain.

The valley produces as much as two-thirds of the country’s winter fruits and vegetables, but sustaining that level of production in a desert has a cost. The Imperial Irrigation District, which manages the canal and the sprawling network of pipes and irrigation ditches it feeds, diverts 2.6 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado, about half of California’s entire allotment from the river. For perspective, it takes about 2 acre-feet to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

The valley’s agricultural boom is what created the Salton Sea. In 1905, flows on the Colorado River were unusually high and the river breached an irrigation canal that carried water to the valley. Unimpeded, the river shifted course toward the dry sink that once held Lake Cahuilla. The canal was fixed in 1907, but by then water covered 515 square miles.

The lake would have eventually evaporated were it not for the wastewater that drained into it, mostly from the surrounding farms. This runoff included enough fresh water to sustain the Salton Sea for decades, but it also brought pesticides and herbicides, including now-banned chemicals like DDT and other cancer-causing compounds, all of which settled in the mud at the bottom of the lake. The inflows varied widely, but sometimes reached as much as 1 million acre-feet a year.

Then, in 2003, the Imperial Irrigation District agreed to agreed to conserve water and transfer the savings to San Diego County. Farmers were forced to abandon flood irrigation, a wildly inefficient strategy that involved flooding the fields and letting the excess run off. Farmers in the valley began using drip irrigation, diverting less river water and allowing San Diego and the Coachella Valley to take the excess. This change meant there was enough water for everyone — but not for the Salton Sea.

“There is this tension because we want to use water more efficiently instead of building more dams,” said Michael Cohen, a senior researcher with the Pacific Institute, an environmental group focused on water policy. “But the unintended consequence of that is that less water goes to the Salton Sea because it is entirely dependent on inefficiency.”

To stave off the lake’s evaporation, the irrigation district continued to put 800,000 acre-feet of water directly into the lake as it implemented efficiency measures. Those water deliveries ended in 2018 and in the coming years the pace of the Salton Sea’s evaporation is expected to triple.

In return for improved water-use efficiency, the state of California was supposed to implement a plan to control dust and reduce habitat loss for migrating birds on the Salton Sea by 2018. But that plan stalled, the lake continues to shrink, and a public-health crisis looms.

A forgotten place

In 2017, researchers from the University of Southern California partnered with the Comite Civico del Valle, an environmental justice group based in Brawley, an agricultural town just south of the Salton Sea for the first comprehensive study of child respiratory health in the region.

The study’s researchers are using data from air quality monitors at schools surrounding the Salton Sea, analyzing the composition of dust coming from the Salton Sea and collecting health data from 500 children in the area to determine how the Salton Sea may change air quality in the region and impact health. Preliminary results confirm the community’s concerns about respiratory problems in children.

The valley’s air frequently falls below federal air-quality standards. One in five children in the area surrounding the Salton Sea have asthma, a rate three times higher than the rest of the state. The reasons for the elevated rates of pollution aren’t fully understood, but it is likely a combination of both natural and chemical dust from farms, the desert and the lake.

“We don’t have any evidence at this point that the existence of the Salton Sea is bad for respiratory health on its own,” said Jill Johnston, one of the researchers on the study, noting that there are a number of factors. “The community is cumulatively burdened, and we know that there are other sources of air pollution going on, but we think that adding in the [Salton Sea] dust without any mitigation can make things worse for children.”

Ryan Kelley, chairman of the Imperial County Board of Supervisors, grew up in Brawley. He was a firefighter and a paramedic before he decided to get into politics. He applauds to efforts of local activists, like Comite Civico del Valle, but says Imperial County has been forgotten by the state and federal governments.

Imperial County has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country, and in 2016 one in four people there lived in poverty. It has some of the worst air quality, too, and the active asthma rate is 12.1 percent, higher than both the state and national averages. But according to Kelley, the county isn’t a priority in the region which includes some of wealthiest communities in the state in nearby San Diego County, the Coachella Valley and Palm Springs.

“When you think of Southern California how often do you think of Imperial County?” Kelley asks. “We don’t have that much in common with San Diego anymore, and our problems get swallowed by these larger, wealthier places.”

What’s happened to the Salton Sea is a case in point. It has been in decline for Kelley’s entire adult life, affecting the health of both residents and the local economy. Tourists are afraid of the potential health issues from the lakebed’s dust and are put off by the frequent odor issues brought on by dying fish. Businesses don’t want to come to Imperial for the same reasons.

Solutions to these problems have been on California’s drawing board for more than a decade and still have not been finalized.

The California Natural Resource Agency released the official Salton Sea Restoration Plan in 2007. The basic premise was to redirect the remaining inflows to the Salton Sea to small, man-made wetlands that would both suppress dust and create bird habitat.

From the outset, the plan lacked funding, and over the years promises of money and action from state lawmakers would arise and evaporate as priorities shifted and water politics changed.

The lack of official action has led to a cascade of alternative plans from environmental groups, advocacy organizations and local governments. Some have proposed piping saltwater in from the Sea of Cortez, desalinating it and returning the lake to its original size. Another plan calls for distributing the water along the lake’s outside to reduce dust, letting the middle dry out. Another group has proposed a complicated strategy that involves releasing foam block islands onto the lake to support new vegetation that would filter salt from the lake. All these plans, including the state plan, lack funding and official rights to any water beyond wastewater.

While there are very real hurdles for moving forward on the plan, Kelley says a lack of political will in Sacramento, the state capital, underlies the failure to act. That may be starting to change.

In recent years, the Imperial Irrigation District, the most powerful entity in the valley, has expressed frustration at the lack of action, suggesting it may abandon the 2003 water-transfer agreement with San Diego County if something isn’t done to fix the Salton Sea.

“The premise in which the [water transfer agreement] was finally agreed upon was having the state of California address the issues of the sea,” said Henry Martinez, the general manager of the Imperial Irrigation District. “There is a question of at what point that agreement is breached.”

Under a new governor, Gavin Newsom, who took office last year, and new leadership at California’s Natural Resources Agency, the state has made some progress on the land-access issues and secured easements to begin some of the dust suppression and habitat restoration projects. Even with this progress, the state is still behind on the planned 10-year project. The government rhetoric has shifted, too, with officials making public statements about the importance of addressing the problems caused by the Salton Sea’s evaporation.

“I can’t really go back and fix the things that happened in the past,” Arturo Delgado, the new Salton Sea Secretary for the Natural Resources Agency told me in November, “but we made a commitment.”

Last Spring, though, the seven states that use Colorado River water agreed to a plan that would reduce the amount of water each would take from the river in certain conditions. Water politics are notoriously fraught in the West, but declining water levels on the Colorado, following a 20-year drought, forced the states and other major users of the river’s water to reach a deal.

Despite pressure from Imperial Irrigation District, the deal did not include money to clean up the Salton Sea.

In October, the Imperial County Board of Supervisors declared a local air pollution emergency at the Salton Sea. In November, the board declared another emergency, this one at the heavily polluted New River, which empties into the Salton Sea. Ryan Kelley hopes to use the local emergencies to cut through some of the red tape holding back the restoration projects. If the state were to declare an emergency, it could secure federal funding and expedite the permitting process.

Delgado says the state is reviewing the board’s declaration but has not yet decided whether to move forward with it. Meanwhile, the lake continues to dry up at a faster rate than ever before.

“There was always a concern that when water stopped flowing to the Salton Sea that it would have an effect,” says Henry Martinez. “Fast forward to what is happening today. It appears we are at least getting close to the tipping point.”

Correction: The story has been changed to reflect the fact that the Imperial Irrigation District did not transfer a portion of its rights to the Colorado River water to San Diego County in 2003. Rather, the IID agreed to be more efficient in its water usage and send the conserved water to San Diego County.

You made it this far so we know you appreciate our work. FERN is a non-profit and relies on the generosity of our readers so that we can continue producing incisive reporting like this story. Please consider making a donation to support our work. Thank you.

This story was produced in collaboration with The Weather Channel, where it first appeared. All rights reserved. Reporting was supported by The Water Desk, and aerial support for photos provided by LightHawk. This article may not be reproduced without express permission from FERN, where it was published January 13, 2020. If you are interested in republishing or reposting this article, please contact info@thefern.org.

Longform Story CSS Block