We’ve heard about the deteriorating status of American infrastructure and most imagine crumbling bridges and potholed roads. But there’s another looming infrastructure crisis that’s getting little to no attention—and it will eventually impact everyone: America’s reservoirs are filling up with sediment. Their storage capacity peaked in the 1980s and it’s been going downhill ever since—sometimes with disastrous consequences.

Niobrara, Neb.— Ruth Janak regularly walks along the Missouri River’s edge in the small town of Niobrara, Nebraska, where she lives. She’ll pan the landscape—hoping to find any remnant of the inventory from the service station she ran with her husband, Victor. Remarkably, she finds things—a hydraulic hose, a belt—but there’s a lot that’s missing—workbenches, tires, cabinets, a pop cooler. It’s gone. “Where are they?” she asks, knowing there’s no answer.

When the “bomb cyclone” weather event ravaged areas from Colorado to Nebraska and the Dakotas last spring, the Spencer Dam on the Niobrara River failed, sending not only a wall of water, debris, and sand downstream but also huge chunks of ice as big as bulldozers. Like a battering ram the flow shoved everything into the river from propane tanks to cattle—and unfortunately for the Janaks—their business.

Standing in a new location higher up in town where they’ve recently moved, Ruth pulls out her phone and shows a video taken by an employee of the Nebraska Department of Transportation, which shows buildings helplessly surrendering to the ice-filled, brown, churning waves and untethering from their foundations, passing treetops as they float out of view.

“The craziest part about it,” she says, “is that our business wasn’t in the floodplain,” adding quickly, “but I’m sure that’s going to change.” It’s a sober recognition that the epic storm will not only likely shift the demarcation for flood hazards—but also be the boundary she’ll remember between her old life and new.

The Janaks weren’t in the floodplain—technically that is—but changes to Missouri River since the last century have blurred the lines of where the government says water officially goes and why. Huge amounts of sand and silt have been accumulating in the river—especially near where the Janak’s business sat at the confluence of the Niobrara and the Missouri Rivers. The more sediment piles up there, the higher the waters rise—something Ruth has witnessed firsthand. When she and Victor bought their business, the water wasn’t even close to them. With increasing siltation, she says, “It knocks at your back door all the time.”

Clear as mud

Sedimentation occurs when all the sand, silt, rocks, and soils that would naturally travel down rivers to the sea get trapped behind dams. Sediment itself is a good thing. It creates habitat, fertile farm fields, and forms deltas at the river’s mouth that are natural buffers against storms in places like Louisiana. But when dams were built along the Missouri River, that natural process came to an end and the troubles began.

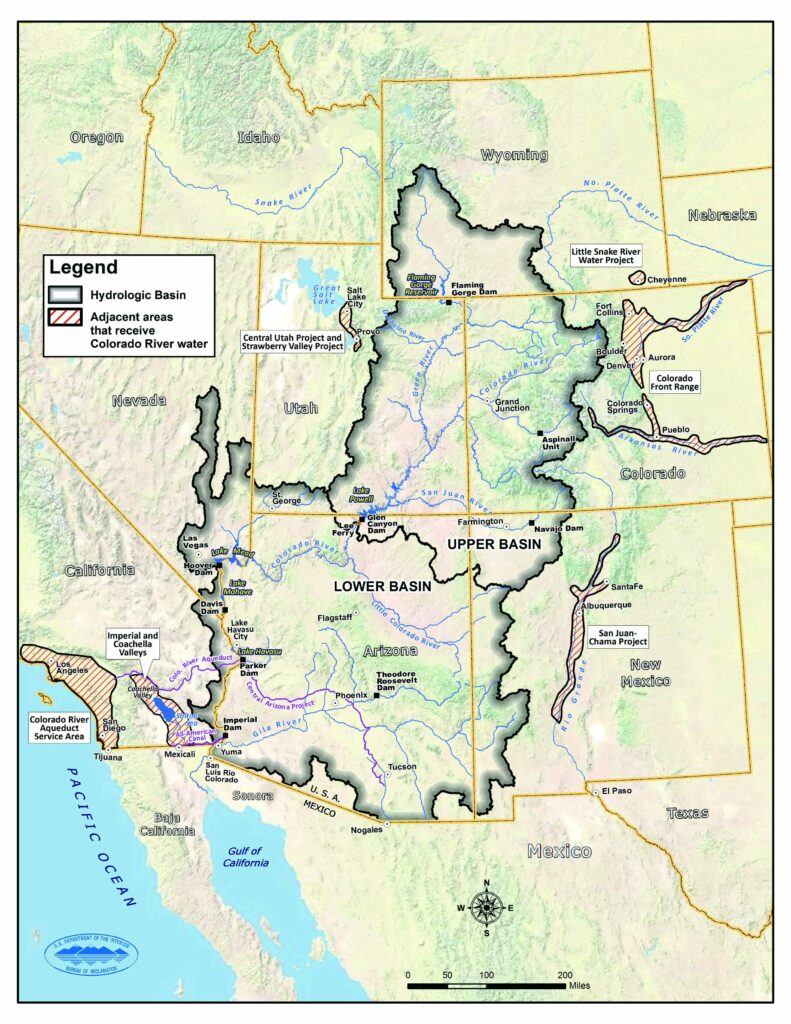

Perhaps nowhere is sedimentation more evident than at the confluence of the Niobrara and Missouri Rivers, where the water snakes its way through lumps of grass-covered islands. The sand has piled up there ever since the completion of the Gavins Point Dam just downstream. When the sediment-laden river hits the deep standing water of its reservoir, called Lewis and Clark Lake, the water loses its energy and the load it’s carrying drops out.

Over time, the sediment mounds up to form a delta and the river is forced to go over, around, or even under it. That happens rain or shine, but during a major flood disaster, like the recent bomb cyclone, levels are pushed up proportionately, if not higher—a point the catastrophic flooding from the Spencer Dam failure made all too clear, says Nicholas Pinter, professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Davis. He says that sedimentation caused by Gavins Point Dam made the destruction of the Janak’s property more likely—“absolutely, unquestionably—and no honest person in the Corps or otherwise would say not.”

The “Corps” he’s referring to is the Army Corps of Engineers. They built Gavins Point Dam in 1955, but in the 1970s they had to move the town of Niobrara because sedimentation resulting from the dam’s reservoir was raising the water table, causing flooded basements and ruined crops.

Actually, the town of Niobrara had to be physically moved—twice. The first time was in 1881 when an ice jam on the Missouri flooded the village with nearly six feet of water. The townsfolk pulled its buildings by oxen and mule a mile-and-a-half to higher ground where they thought they would be safe. But that was before Gavins Point Dam was built.

No one disputes that the reservoir was responsible for the high groundwater in Niobrara in the 1970s. In fact, the engineers who built the dams in the 1940s and ’50s along the Missouri River knew sedimentation would be a consequence. But, says Pinter, Gavins Point Dam was “designed as almost every large dam on Earth, which is not to say that it was well designed or poorly designed, but it was well known at the time that it would not pass the sediment that it would need to, to avoid this problem.”

A sediment design life

The fact that the dams would not pass sediment—and that eventually sedimentation would make them inoperable—was not only fully acknowledged by the engineers who designed them, but they even had a name for it—the “Sediment Design Life.” As Tim Randle, Manager of the Sedimentation and River Hydraulics Group at the Bureau of Reclamation explains, “Virtually all reservoirs in the U.S. and much the world were designed with a sediment design life, meaning after so much time the reservoir’s not going to function very well, the outlet will be plugged.” For Reclamation and Army Corps dams, he says, that lifespan was somewhere around 100 years.

Since many large dams were built in the middle of the last century, they are now in the second half of their sediment design life. Some might fill in decades, others in hundreds—or even thousands of years. Which ones? That’s hard to know, says Randle. Most reservoirs—65 percent of Reclamation reservoirs—haven’t been surveyed for sedimentation since they were filled.

Randle says long before reservoirs completely fill there will start to be problems like dam outlets or hydropower intakes getting gummed up, as well as boat ramps or marinas getting buried—and as was the case in Niobrara—floods. There are over 90,000 dams on the federal inventory—so any notion of just letting the reservoirs fill up and store water elsewhere would be difficult—essentially all the good sites are taken.

The Pick-Sloan Plan…and the rest is history

But history might have taken a different course had Glenn Sloan prevailed. Before the dams were built the sediment-laden “Big Muddy” meandered restlessly from valley wall to valley wall and flooded occasionally. When the Lewis and Clark expedition explored the Missouri River in the early 1800s it was almost a mile wide with numerous sandbars that split the waterway into several braided channels.

But in 1943, three devastating floods put pressure on Congress to tame the river once and for all, and they called on the Army Corps of Engineers to produce a plan. Colonel Lewis A. Pick, then division engineer in the Corps’ Omaha, Nebraska, office, proposed five multipurpose dams on the mainstem of the Missouri River above Sioux City, Iowa.

Meanwhile, William G. Sloan, an engineer with the Bureau of Reclamation, called for over 85 new tributary dams and three mainstem dams. Tim Cowman with South Dakota Geological Survey suggests that by putting smaller dams on the tributaries, they would have captured small amounts of silt and sediment in numerous places, preventing it from reaching the Missouri—and perhaps avoiding the massive sedimentation problem happening today.

In the end, the plans were merged into the Pick-Sloan Plan, which Congress ratified in the Flood Control Act of 1944. The plan brought flood control, irrigation, and hydropower to the basin, but Native Americans, whose reservations bordered the river, were huge losers. The reservoirs flooded their best agricultural and grazing lands and displaced hundreds of families. Attorney Peter Capossela, writes in his article, “Impacts of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Pick- Sloan Program on the Indian Tribes of the Missouri River Basin”:

The trouble below

Meanwhile, the sediment delta of Lewis and Clark Lake grows. It extends, on average, 400 feet per year—and in huge weather events, storms can shove sand and silt nearly a mile into the lake. Cowman says this not only takes up precious storage space but also reduces the reservoir’s ability to handle floods.

But downstream of the dam, he says, there are problems, too. When water is released downriver, it’s clear, having left its trapped sediment in the reservoir. However, the released water actually seeks out sediment, something called “hungry water.” That water satisfies its craving by scouring the riverbed below and eroding its banks. In fact, Cowman says, the channel below Gavins Point has been eroded by ten feet, and that’s recently forced the city of Yankton, South Dakota, to lower its water intake pipes because they’ve become higher than the river’s surface. For comparison, according to the organization International Rivers, “Within nine years of the closure of Hoover Dam, hungry water had washed away more than 110 million cubic meters of material from the first 145 kilometers of riverbed below the dam, lowering it in places by more than four meters.“

Also because the dam controls the river flows—never getting too high, never too low—the natural process that used to build sandbars, stopped. Normally during flood events, Cowman says, high water builds up what are essentially sand dunes on the bottom of the riverbed. Once the water drops to normal levels, those sand dunes become sandbars sticking out of the water. Unless there are occasional high flows, new sandbars won’t form and the ones that are there will erode away. In fact the Army Corps of Engineers was required, at some expense, to build new sandbars because two endangered birds—the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) and interior least tern (Sterna antillarum athalassos)—that nest just below Gavins Point had lost their habitat.

Solutions

Because of these problems both above and below Gavins Point Dam, a group called the Missouri Sedimentation Action Coalition (MSAC) was formed to educate the public about the issue and find solutions before things get even worse. The group reflects a range of interests including individuals, nonprofits, cities, and tribes who are already feeling the effects of sedimentation in Lewis and Clark Lake, which is 30 percent full of sediment and expected to reach 50 percent by the year 2045 if nothing is done.

So what can be done? There are three general strategies to managing sediment in reservoirs. One is to look at the upstream watershed and reduce erosion and runoff to keep debris from entering the river. Tactics include bank stabilization efforts and buffer strips, to better farming practices and keeping livestock from grazing too close to a waterway.

Another set of solutions is to prevent sediment from depositing in the reservoir by routing the silt and sand through or around the dam. This can be achieved with tunnels or channels that bypass the sediment around the reservoir, or with sluicing methods that move sediment through the dam before it has a chance to deposit.

One mechanism that MSAC is evaluating is to create a sort of speed bump in the river channel with something called “sediment collectors,” which entails putting a metal trough (or a series of troughs) across the riverbed. The collectors would passively create a difference in the speed of the current as it passes over it and a substantial amount of sediment would drop into the trough, where it could then be augured out and up onto land. However, what to do with all that stockpiled sediment would be an issue.

The third approach is to remove sediment that has already been deposited in the reservoir either by dredging or flushing. The issue of what to do with all the material is also a question, particularly if contamination is suspected.

SOS

Any of the sediment management solutions will be costly, take time to implement, and have engineering challenges. Tim Randle and his colleagues are part of a group called the Subcommittee on Sedimentation, which ironically has the acronym “SOS.” In 2014 they put out a resolution [Full text] calling on all federal agencies that own or operate dams to come up with sustainable management plans for reservoirs by 2030 and that the plans “should include either the implementation of sustainable sediment-management practices or eventual retirement of the reservoir.” That was five years ago and not much has happened. [See June 2019 National Reservoir Sedimentation and Sustainability Team white paper.]

Sedimentation is not just a problem for Niobrara, or even just the Missouri River. It threatens nearly every major reservoir in the U.S. And although what happened to the Janaks is in the extreme, it could be a harbinger of what’s to come if the issue is not addressed.

MSAC is adamant that doing nothing is not an option. Sandy Stockholm, executive director of the organization, says they are working with their stakeholders, the Army Corps, and several experts from academia with the goal to finalize the scope of a sedimentation management plan by the end of the year. The resulting plan—if they can fund and implement it—will not only slow the damage but also become a model for reservoirs across the country, which, whether dam owners know it or not, are on track to have the same fate. ?

This story originally appeared on H2ORadio.org and is republished here by permission.

The Water Desk’s mission is to increase the volume, depth and power of journalism connected to Western water issues. We’re an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Water Desk launched in April 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundation. We maintain a strict editorial firewall between our funders and our journalism. The Water Desk is seeking additional funding to build and sustain the initiative. Click here to donate.